Animation scripted by Dr Jonathan Bardon

Firebombed, flattened and forsaken

Belfast was one of 16 cities across the UK to suffer as a result of the Biltz, the name given to the bombardment of urban areas by the German air force in World War Two. The Luftwaffe carried out four raids on the city between 7 April and 6 May 1941, leaving over 1000 people dead. Apart from London, this was the highest casualty rate per raid, indicating the lack of readiness for such events.

Tens of thousands more fled. Some to the hills surrounding Belfast, others further afield. Belfast was important to the Germans as it was used to repair ships and produce aircraft for the Allied war effort. Several sites that were strategically important were hit. In short, the Blitz had a devastating effect on Belfast, which had been utterly unprepared for such a major attack.

Unprepared

Northern Ireland was ill prepared for the Luftwaffe's arrival. Ministers felt it unlikely that the bombers could reach Belfast from their bases in Northern France.

The government at Stormont had provided only four public air raid shelters in Belfast, and most of the city's searchlights had been sent back to England.

In fact, over 1000 people from England had been evacuated to Belfast because it was felt to be so safe.

There were plans to evacuate 70 000 children from Belfast, but little over 10% of that number actually left as a sense of distance from the war set in.

When an unobserved German plane flew over Belfast to identify targets in November 1940, it saw a city defended by only seven anti-aircraft batteries.

The first raid

At midnight on Monday 7 April 1941, German planes began bombing Belfast targets that had been identified the previous year. Having broken off from a raid on Glasgow, seven German bombers attacked the docks and shipyards with alarming accuracy.

The fuselage factory at Harland and Wolff was hit by a parachute mine, destroying 50 Sterling bombers. Incendiary bombs and high explosives also destroyed houses in north and east Belfast.

By the time the raid ended at around 3.30am, 13 people had been killed. Whilst this had been a shock to the people of Belfast and the Northern Ireland government, they didnÔÇÖt realise that the air raid of 7 April had been a very small one.

The Germans had only been testing Belfast's defences. Life returned to normal and the population were preparing for the Easter holidays. However, much worse was to come in the following weeks.

The second raid

The sky was clearing in Belfast on Easter Tuesday, 15 April 1941, as 180 German bombers took off from aerodromes in Northern France to launch a full raid on the city.

The pilots were determined and in high spirits: "We were in exceptional good humour knowing that we were going for one of EnglandÔÇÖs last hiding places. Wherever Churchill is hiding his war material we will go. Belfast is as worthy a target as Coventry, Birmingham, Bristol or Glasgow."

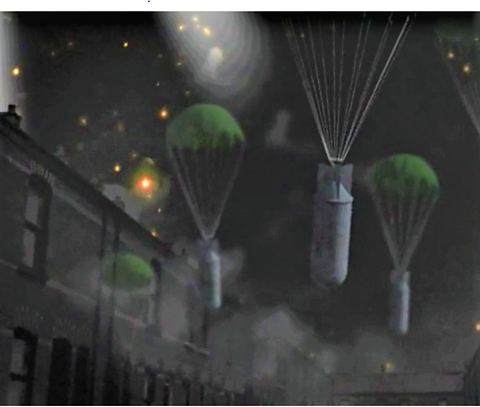

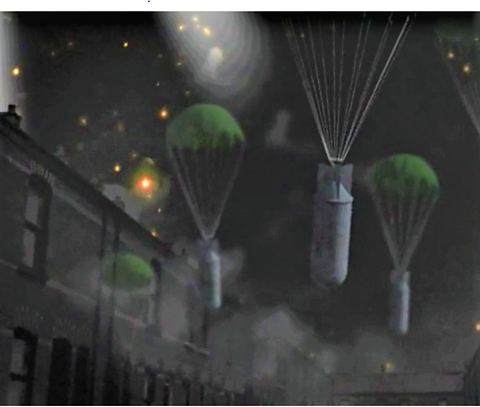

The amassed squadrons flew along the Ards Peninsula and approached Belfast by Divis Mountain. At 10.40pm, the wail of air raid sirens began to be heard around the city. Belfast had been lit up by hundreds of flares as the Luftwaffe aircraft dropped a barrage of incendiaries, high explosive bombs and parachute mines.

It must have seemed very strange for the locals to see the little parachutes drift down so gently, only to unleash their deadly, destructive cargo.

Civilians suffer

The civilian population was particularly affected by this raid as the main strategic targets were, in large part, missed. The historian Chris McGimpsey wrote that ÔÇťby 4.00 am the entire north of the city appeared to be ablazeÔÇŁ as the Shankill, New Lodge and Antrim Road areas, with their densely packed housing, took the brunt of the bombings.

The rescue and defence operation were cruelly hampered by the destruction of the Central Telegraph Exchange. This meant that communications with Britain and the local military defences were cut off. Additionally, cracks to the water mains led to a lack of water to supply the hoses of the fire crews, desperately struggling to save the burning buildings.

The government at Stormont asked Eamon De Valera, the leader of the Irish Free State, for help. De Valera immediately dispatched fire crews from four sites to assist the effort in Belfast.

Long after the last German plane left at 4.55 am, the fires in Belfast still burned and its citizens were starting to come to terms with the incredible devastation wrought upon their city.

More on The Belfast Blitz

Find out more by working through a topic

- count2 of 4

- count3 of 4

- count4 of 4