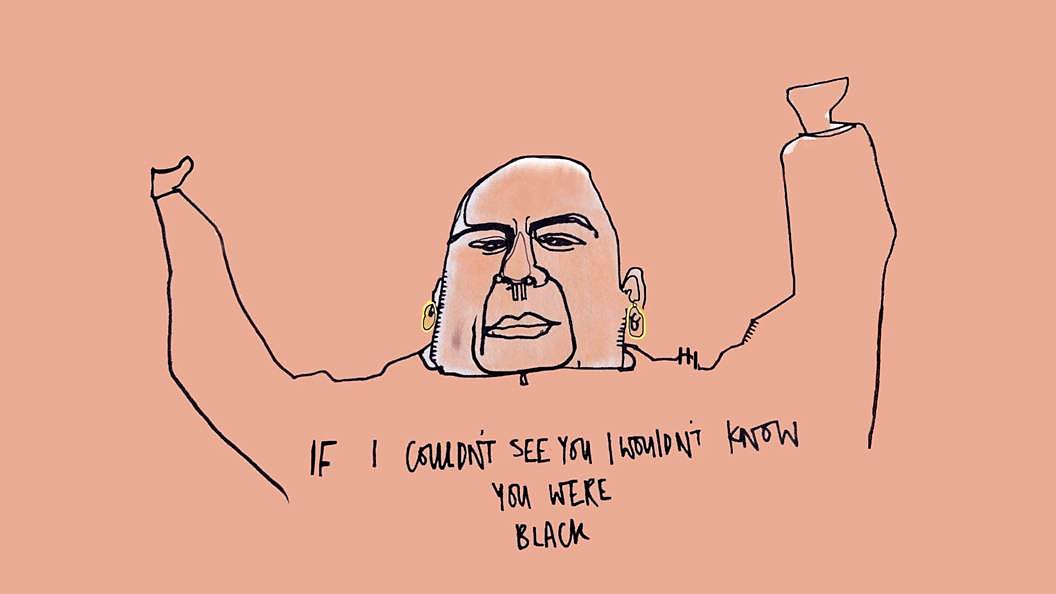

"Microagressions are the insidious side of racism"

Illustration by Leyla Reynolds

- Published

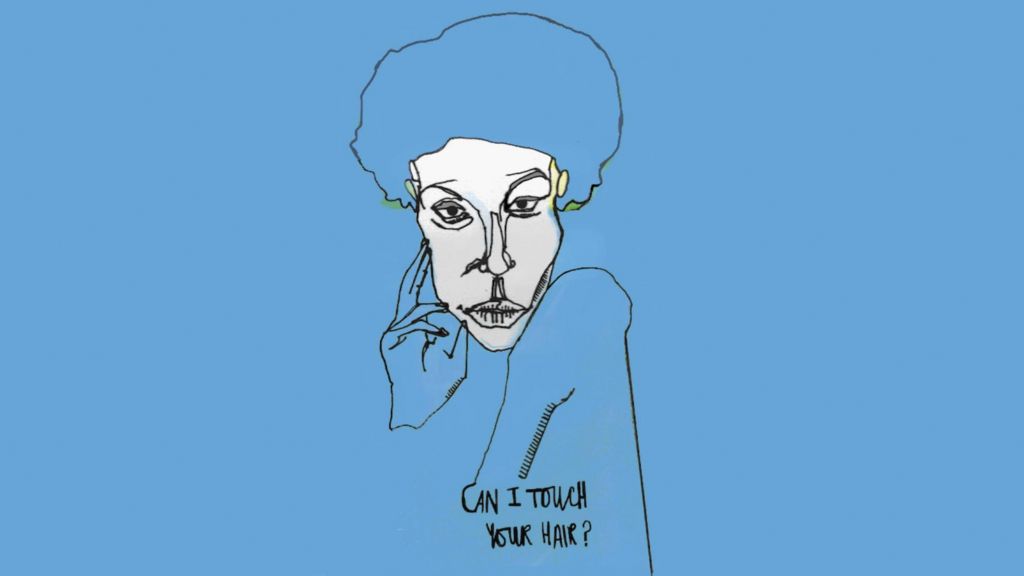

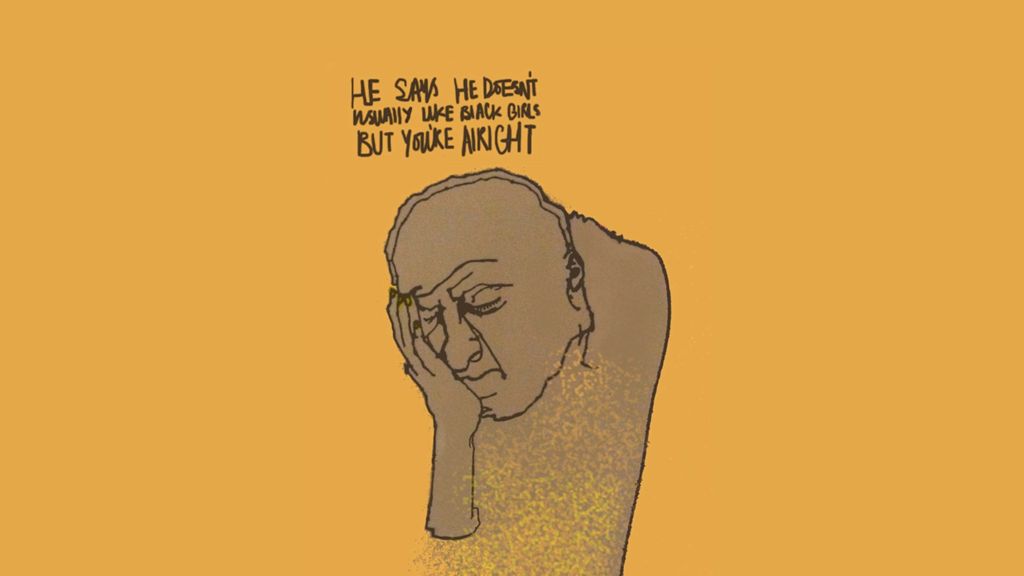

As a mixed-race black woman, the way I usually experience racism can only accurately be identified through the use of the label microaggressions. It has given me the ability to succinctly verbalise the fact that being told that I behave 'too white' to call myself black is inappropriate; that being asked, ‚Äúwhere are you from?‚ÄĚ before any other conversation begins is unnecessary and isolating; and that having someone pull on my braids to get my attention, as if they are not attached to my head, is rude on more than one level.

One project that seeks to combat these kind of microaggressions is 'I'm tired', 'I’m tired of being the angry black woman', or 'I’m tired of people judging me for my weight', painted onto people’s backs and captured in monochrome in an attempt to tackle a problem which has only recently been given a name.

Allow Twitter content?

This article contains content provided by Twitter. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read and before accepting. To view this content choose ‚Äėaccept and continue‚Äô.

Microagressions are slights and snubs experienced by marginalised groups. From a black man seeing someone crossing the street to avoid him out of fear, to a disabled person being labelled inappropriately as 'handicapped'.

The project tackles issues relating to transgender people and , to ableism and mental health.

‚ÄúYou think you have a grasp on it, that you‚Äôre quite socially aware, but you can never be too socially aware,‚ÄĚ says founder Paula Akpan, speaking to me on the phone from New York, where the 'I‚Äôm Tired' project recently held their first exhibition.

Allow Twitter content?

This article contains content provided by Twitter. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read and before accepting. To view this content choose ‚Äėaccept and continue‚Äô.

That’s not say I haven’t experienced overt racism too - hate crime does happen in the UK more often than many people realise - but it's the insidious, everyday nature of microagressions that are so disruptive.

My mother, who grew up in the 1960s-era of 'no blacks, no dogs, no Irish'¬†signs being plastered on the front of properties for rent, and who is many shades darker than I am, has spoken far more often about having shopkeepers avoid touching her hands when giving her change than being called ‚Äúrubber lips‚ÄĚ at school.

But the explosion of the use of the term, which began on university campuses in the USA, has met with its fair share of criticism.

‚ÄúIn the UK, the denunciation of microaggressions has seamlessly meshed with the obsessive search for harmful gestures and words associated with everyday sexism and everyday racism,‚ÄĚ writes Frank Furedi for online current affairs magazine¬†'Spiked'. ‚ÄúIt is only a matter of time before the ‚Äėeveryday outrage‚Äô movement is launched to cover the entirety of everyday life.‚ÄĚ The right-wing media have consistently equated microagressions to a rise in 'victimhood culture', dismissing it an example of ‚Äúidentity politics‚ÄĚ.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read and before accepting. To view this content choose ‚Äėaccept and continue‚Äô.

Journalists have argued that the word is a symptom of a culture where everyone wants to feel hard done by, while social scientists in the US have said, ‚ÄúAccording to the most basic tenets of psychology, helping people with anxiety disorders avoid the things they fear is misguided.‚ÄĚ

My guess is that many of those who have criticised the term are white heterosexuals; the same people who dominate the journalism industry, sit on the boards of companies which have huge gender disparity, and have likely not been on the receiving end of microagressions. Their lack of understanding, while unsurprising because of these factors, only serves to silence minority voices.

Rather than allowing 'victims' to ‚Äúavoid the things they fear‚ÄĚ, I believe acknowledging microagressions signals a positive change in our culture. We seem to be¬†reaching a stage where minority groups are unafraid to speak up, in no small part thanks to the platform for dialogue that the internet has provided. To attempt to counter that dialogue with misguided egalitarianism is an unfortunate but unsurprising tactic from the type of people who claim that they ‚Äúdon‚Äôt see race‚ÄĚ, but are happy to reap the benefits of their privileged existence. And although you can‚Äôt win everyone over, in my opinion, recognising microagressions means that they can ultimately be used to educate.